What is a Use Specification?

A Use Specification is a document defined in EU Guidance 62366-1 to summarise the important characteristics related to the context of use of a medical device. In short it likely contains at least the following information:

- What is the intended use of the device?

- Who are the intended users?

- Where is the device intended to be used?

- How is the device intended to be used?

Accurate definition of these topics are key for the medical device development process. Understanding these will ensure that devices are accommodating of the variability and limitations of device uses, users and use environments. In addition, before market approval, the user interface of a medical device will likely need to be validated within simulated conditions that are sufficiently representative of these characteristics.

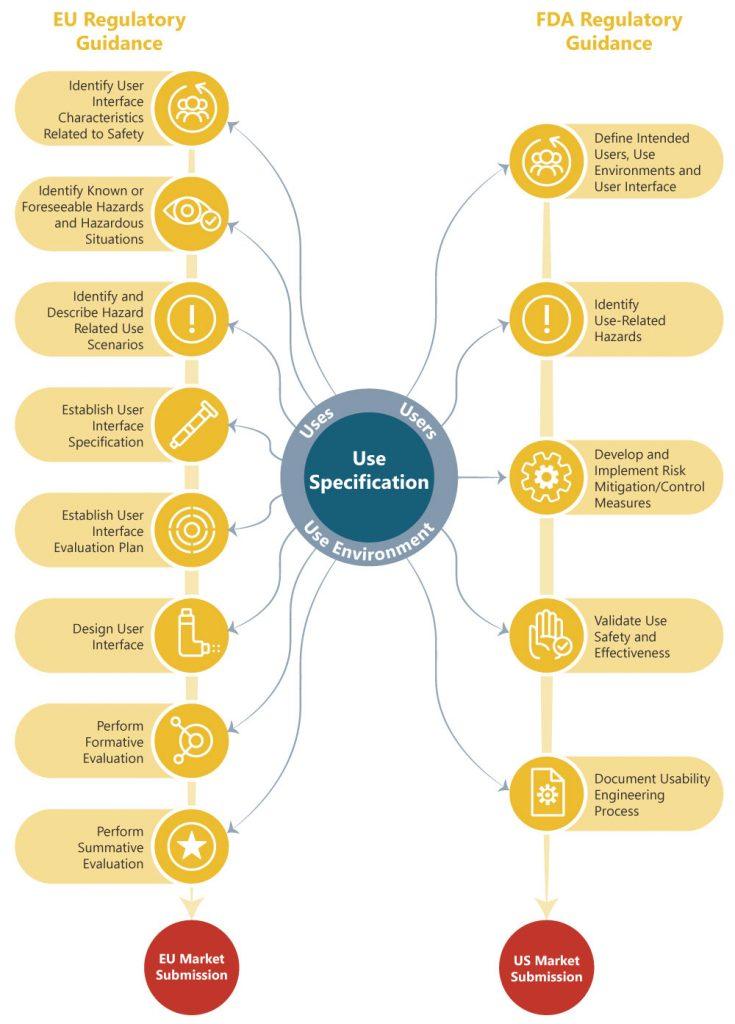

Whilst the FDA guidance does not call out specifically for the Use Specification, it is expected that medical device manufacturers will have considered the same characteristics of use prior to conducting human factors or usability engineering analyses.

The impact of the information contained within the Use Specification on other Usability Engineering File Deliverables required by EU and FDA regulators is illustrated below.

Theory vs. Reality

As a usability consultancy for medical devices, Rebus is, unfortunately, often engaged at relatively late stage in the design process. We find that, whilst most of our clients often have an emersed understanding of for what, whom and where they are designing their medical devices, the Use Specification is often written as an afterthought to meet the regulator’s requirements prior to a regulatory submission.

It is tempting to get stuck straight into the concept generation, not getting ‘bogged down’ in documentation too early and to remain ‘dynamic’. However, a Use Specification can ultimately make the initial research process more efficient if considered early. This can help avoid costly redesign, due to design and user requirement divergence, and ultimately benefit all end users with an effective and satisfying product.

You can still be agile – the Use Specification is a live document and so only needs to reflect what you know at the time, meaning that the first draft can be quickly generated then iterated and improved alongside product development.

Efficient user research

In the case of novel medical device design, knowledge about the use conditions of the medical device might be limited in the concept generation phases. To support the knowledge development exercises, project managers and designers might use tools such as contextual inquiry, interviews with potential users or informal discussions with key opinion leaders.

Drafting a Use Specification, especially from a template with all of the information that regulators ultimately expect to see, will provide an opportunity for the team to recognise what it is that they do not know. Gaps in the document provide a foundation from which to drive user research in the right areas, with the right people and the right questions. This is particularly crucial when budget, timeline and resourcing constraints might limit opportunities for additional research. If additional research is done much later in the project, the impact of learning points may be significantly reduced or the cost of design changes significantly higher.

In the case of a modification to a device that is already on the market, there is likely a wealth of information available. A Use Specification may serve as a useful pin board to collate input from representatives from Sales, Marketing, Clinical and Regulatory specialties within the company to maximise the benefit for their diverse experience and knowledge of the market.

A word of caution however. Whilst it may be tempting to combine sales, marketing and user research efforts, ensure that these activities do not negatively affect each other as their subject matter is similar but their goals are different. For example, it may be conflicting to have a fully open discussion about a device’s failures whilst also trying to maintain brand confidence. User research should be conducted with a usability engineering focus.

Linking research with designers

The power of good user research lies not in carrying out the research but in the communication of its considered conclusions. Designers of the medical devices are often at least one step removed from the clinical use of the devices that they are developing. A Use Specification provides a tool to give those that are integral to the development of the devices both insight, and a reminder of the devices intended uses, users and use environments.

A Use Specification can be developed with the project team, embellishing it with brainstormed user profiles, personas and user journeys. Whilst having designers visit the use environment in person is ideal, photos of the use environments are a productive substitute. Consider for example having designers run through a mock procedure using the devices, walking in the shoes of the user based on the information presented within the Use Specification; this can be done in the form of a cognitive walkthrough.

As the project grows, teams are often expanded. The Use Specification can provide an excellent resource in introducing new members to the project, getting them up a steep learning curve faster. Going forwards, the Use Specification can provide a useful touchpoint for Project Leads to ensure that all factors have been considered during the user interface development and that scope creep is suitably rationalised against a common reference point.

Design for all the right people and environments

Whilst design effort is often focussed on the primary use of the device, complimentary uses of the device (such as installing, cleaning, moving and maintenance) should also be considered early. This leads to a holistic design process where optimal design solutions to meet use requirements can be implemented whilst there is the greatest opportunity to do so.

In addition, design decisions can be well-served with a reference to the characteristics of the user population. For example, an understanding of functional capabilities (physical, sensory and cognitive) and cognitive abilities (including education, experience level, language and literacy) can help ensure that the device is designed with a minimised opportunity for use error.

If the level of training that users are expected to receive is considered early, there may be opportunities to incorporate training into the device. An example of this might be a defibrillator which guides the user with audio and visual cues through a stressful, life-critical process where prior training is easily forgotten.

Use environment factors such as lighting level (low or high), noise level or the presence of similar devices are worth recognition in the early design phases to minimise opportunities for use error when the environment is replicated in a simulated-use validation study as one of the final usability hurdles of a regulatory submission.

Putting the Use Specification into effective practice

The Use Specification should be started early in the medical device development process and will likely start as a top-level collation of what is known about the device’s intended use, users and use environment. It is recommended that a template is used to provide consensus of what is known and what is yet to be discovered and understood; it is ok if the first draft has lots of gaps! The Use Specification should develop over time in detail and accuracy, with focussed user research and organic knowledge development over the project life cycle. Opportune times that the Use Specification may be updated during the development process include after user research activities, prototype review with potential users or clinical trial activities.

If the Use Specification can become a lighthouse for designers to seek throughout the development process (and is maintained as such), it’s due consideration will maximise likelihood of the device ultimately meeting its regulatory usability requirements and becoming a successful and satisfying medical product.

Written by Charlie Irving, Senior Human Factors Consultant.